“In China, fan meetings are allowed, but no singing or dancing. You have to fill the time with talk only,” said one management PR staffer. Another label rep added, “China shows aren’t over until they’re over. Look at 'Dream Concert'—canceled just days before.”

Despite sporadic fan-meeting activity prompting talk of a thaw, industry sources say the unofficial “K-content curb” still operates. They describe on-the-ground “guidelines” that keep restrictions in place: bans on performing Korean-language songs, limits on Korean actors appearing on Chinese stages, and exclusions aimed at dual-nationality singers. Behind that, they cite denials of performance visas, venue-rental hurdles, and language rules—an “invisible wall” that still works.

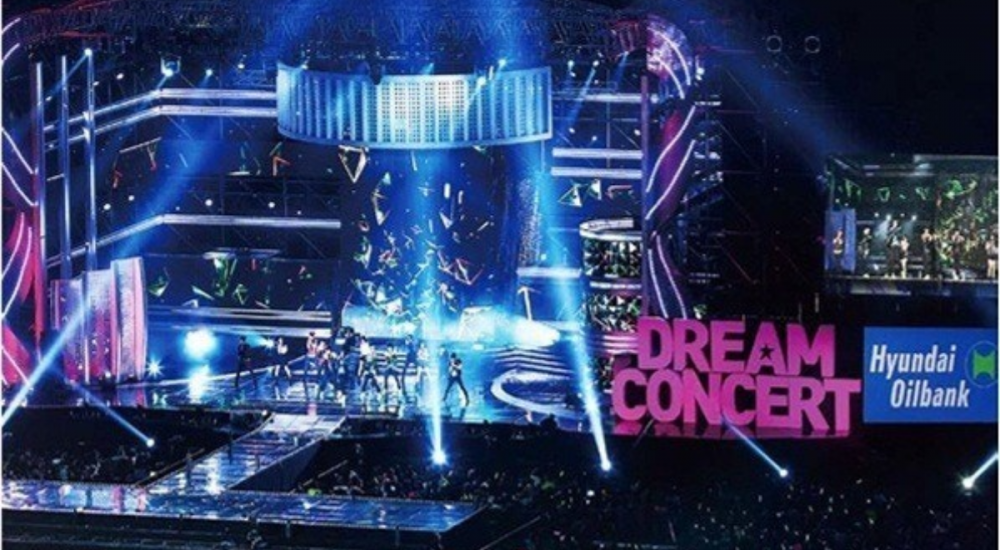

Earlier this month, the large-scale 'Dream Concert'—billed as the biggest K-pop show in China in a decade and slated for late September 2025 at Sanya Sports Stadium (capacity about 40,000)—was postponed only a few days before showtime. Kep1er’s Fuzhou date set for September 13, 2025 was also abruptly canceled for “unavoidable reasons.”

As attention grew, a question at the September 17, 2025 Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs briefing asked whether South Korea’s entertainment industry still faces constraints entering China. Spokesperson Lin Jian said China had no objection to “healthy and beneficial” bilateral cultural exchanges, but on 'Dream Concert' and Kep1er specifically, “we are not aware of the details.”

The informal curb dates to 2016, when Beijing responded to the THAAD missile-defense deployment by limiting Korean music, TV, and film. The last major K-pop concert held in China before that freeze was BIGBANG’s 2016 tour. Many therefore read the planned 'Dream Concert' as a potential, if unofficial, signal of easing.

Analysts point out that Beijing publicly denies any ban while practical constraints persist—curbing Chinese tourism to Korea, throttling distribution of Korean content in China, and so on. Meanwhile, demand inside China never disappeared; viewers have continued to access Korean series and films through illicit platforms, even for titles officially unavailable on local services.

On the ground, promoters say uncertainty has bred opportunists. With permits not yet issued, unsolicited “offers” arrive to book artists, while some fix dates and venues and begin selling tickets in China based only on proposals floated in Korea. When events collapse, the heaviest damage lands on artists and IP-holding content, driving Korean management and producers to adopt a more cautious stance.

Observers add that Beijing increasingly frames cultural content as a national-security domain, viewing the Korean wave as foreign ideological influence. Because controls are informal, authorities can maintain deniability while preserving leverage. With China’s own content industry now far stronger than a decade ago, the competitive gap has narrowed, and even a formal easing would not guarantee a return to past market share. Still, if curbs were lifted, some segments could benefit: expanded licensing for dramas and films, restarted K-pop touring and merchandise sales, and more game licenses.

For now, import decisions are expected to remain highly selective and aligned with policy. As one industry contact noted amid a rise in China-related meetings, “We all learned from the curb that in China the market can change overnight with policy. It’s a market you cannot ignore, but we’re approaching it far more carefully to reduce uncertainty.”

SEE ALSO: Yoo Jae Suk opens up about scary on-set accident and plastic surgery treatment

SHARE

SHARE