Everyone said it wouldn’t work—but one Korean film has pulled off a stunning global upset.

Amid the overwhelming flood of content, 'The Great Flood,' a Netflix original starring Kim Da Mi and Park Hae Soo, has managed to break through worldwide.

According to the global OTT ranking site FlixPatrol on December 30, 'The Great Flood' shot straight to No. 1 in Netflix’s global film category immediately after its release on December 19 and has held the top spot for nine consecutive days. From day one, it surpassed major international titles such as 'Knives Out: Wake Up Dead Man' and has remained firmly at the summit. Given how rare it is for a Korean film to maintain No. 1 in Netflix’s global movie rankings for an extended period, the achievement itself is notable.

The Great Flood begins with a catastrophic premise: a meteor collision causes glaciers to collapse, submerging most of the Earth underwater. The apartment complex where the protagonist, Gu Anna (played by Kim Da Mi), lives is rapidly flooded. Holding the hand of her son, Shin Ja In (played by Kwon Eun Sung), Anna attempts to evacuate to higher floors, only to find the stairwells already jammed with residents. At that moment, Son Hee Jo (played by Park Hae Soo), an infrastructure security officer from the research institute where Anna works, appears and guides her toward an escape route, saying a helicopter will land on the rooftop.

The film’s early portion follows familiar disaster-movie conventions. With the lower floors completely submerged, some residents prepare for death, while others offer shelter and water to strangers. Scenes of a pregnant woman giving birth are intercut with looting in abandoned apartments, contrasting different facets of human behavior in crisis. Director Kim Byung Woo once again employs the claustrophobic tension and anxiety he showcased in The Terror Live, repeatedly using confined spaces to heighten unease.

Midway through, however, the film sharply pivots into a science fiction narrative, defying audience expectations. Anna learns that she is a key figure in developing the “Emotion Engine,” a project designed to teach emotions to a new humanity in preparation for human extinction. Completing this mission requires her inevitable separation from her son. From there, the story portrays the process of converting emotions into data for AI learning as a series of quest-like tasks.

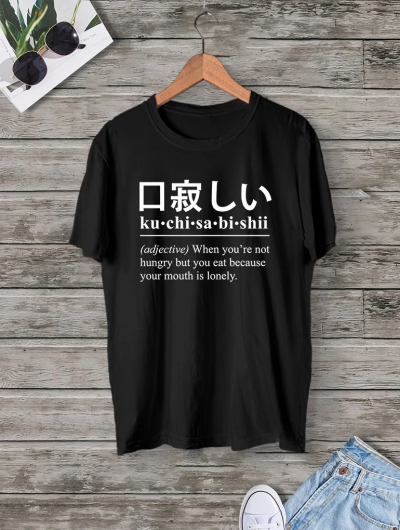

Exposition is kept deliberately minimal. Anna’s profession and mission are conveyed indirectly through repeated visuals and dialogue, and viewers must infer which experimental phase they are in by the numbers printed on her T-shirts. This lack of hand-holding became a decisive point dividing audience reactions.

Although the film launches with multiple themes—climate disaster, AI replacing humanity, and time loops—it ultimately converges on a single emotion in the latter half: maternal love. While the VFX vividly captures the terror of surging waters and the actors’ physically demanding performances, much of which involved prolonged water-based shoots, some critics argue that the thematic expansion remains limited.

This structure contributed to a lukewarm domestic response. On Naver Movies, the audience rating hovered around 4.13 out of 10, accompanied by harsh criticism of the film’s overall quality. Yet global viewing data tells a very different story. On FlixPatrol, 'The Great Flood' ranked No. 1 in 72 countries across both English- and non-English-speaking markets, making it the most successful Netflix-released Korean film to date by that metric.

Why the stark contrast between low domestic ratings and high global rankings? Analysts point to Netflix’s consumption model, where regional taste differences are immediately reflected, and to the universal appeal of disaster and sci-fi genres, which lower language barriers. Kim Da Mi herself noted in an interview that the disaster theme may have resonated with audiences worldwide.

Among critics, assessments have been more measured. Heo Ji Woong commented on social media that the film is being excessively criticized and argued that its underlying questions are meaningful. Director Kim Byung Woo also emphasized in interviews that the film’s core question is “What is love, and where does it come from?”, underscoring his focus on emotion and human relationships.

Symbols visualizing these themes are scattered throughout the film. Stickers of dinosaurs and peacocks on Gu Anna’s face symbolize evolution and extinction, later replaced by rocket and helicopter stickers that suggest humanity’s choices and movement. The name Shin Ja In is designed to represent a new generation of humans, while Son Hee Jo is described as a character projecting an alternative future of what an abandoned child might become.

Technically, the most demanding sequence is the “Room 702” scene, created using a dry-for-wet technique. Filmed without actual water and realized through wires and CG, it took the longest to complete, requiring actors to perform as if submerged. Kim Da Mi appears in 112 out of 115 total shooting sessions, spending most of the production soaked. Due to safety concerns during water scenes, frequent breaks and reshoots were unavoidable.

Regardless of debates over its artistic merits, The Great Flood’s global success illustrates how Korean films are consumed on Netflix. The gap between theater-centered critical evaluation and OTT viewing metrics, combined with the international universality of disaster and sci-fi genres, makes this achievement significant not only culturally but also from an industry perspective.

SEE ALSO: Hyolyn reveals healthy, confident look in new photos showing tattoo over surgery scar

SHARE

SHARE